Spaceballs the Datacenter!

Published on

At 10,302 words, this post will take 41 minutes to read.

I love Spaceballs. Growing up, it was my favorite Mel Brooks flick. Watched it every birthday. To this day, I can quote the entire movie. That’s not an exaggeration. Ask my wife.

It’s the absurdity of it. The delight of Mel Brooks’ clean, self-deprecating, sophomoric satire. No one is spared ridicule. It punches up (unlike so many “comics” and famous people these days who like to punch down). By the way, if you want a real treat, read Brooks’ autobiography, All About Me!

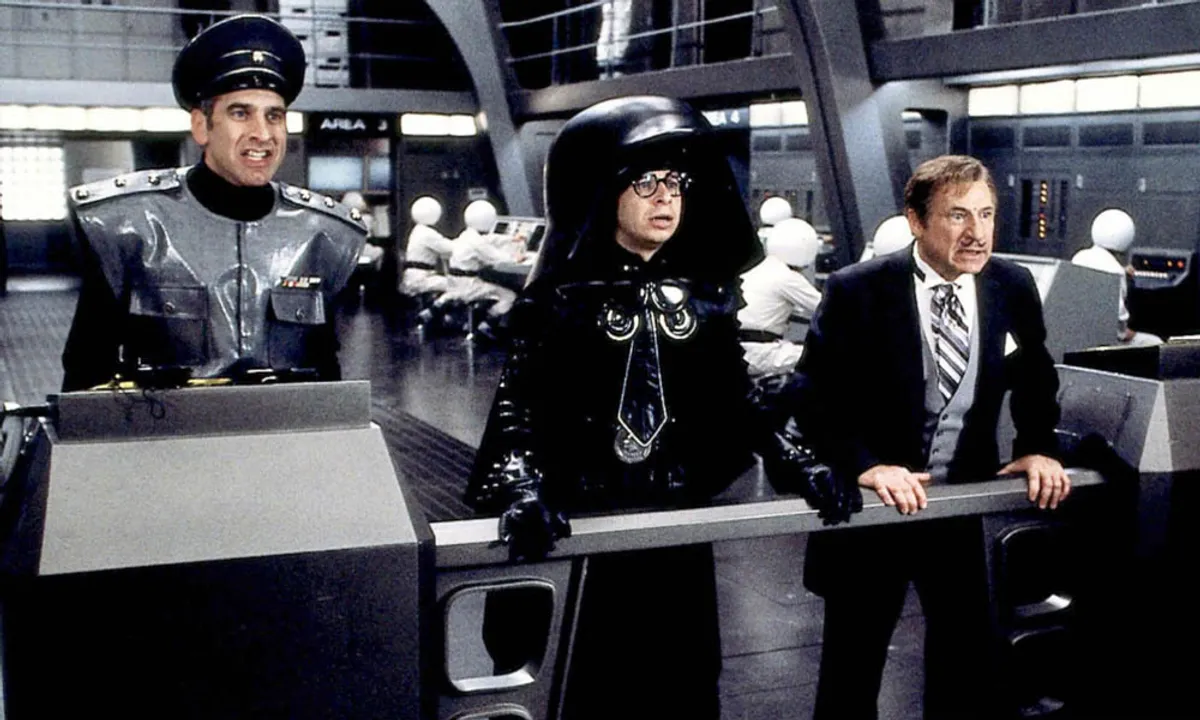

This xAI–SpaceX datacenters-in-space merger, and the subsequent breathless reporting by everyone from the Wall Street Journal to your favorite neighborhood newsletter, reminds me of a Spaceballs bit. Actually the entire plot of the movie… the Spaceballs are going to suck the atmosphere from Druidia with Mega Maid™, a gargantuan space-based vacuum cleaner shaped like a maid (and vaguely reminiscent of the Statue of Liberty for the final homage to Planet of the Apes). Musk’s claim makes less sense than this plot.

And I’m going to show you. With MATHS.

I love math and physics. You can’t beat it. Literally. There’s no way around the gravitational constant, the speed of light, Boltzmann’s constant. If someone can prove, mathematically, that what you’re trying to accomplish is bubkis, well, you’re screwed.

Hold tight. It’s about to get mathy in here.

Part 1. Making an Ass out of You and Me.

We need to make some assumptions. We don’t have to, but then no one would read this. To make this more approachable, and, more importantly, to avoid pissing off my wife by spending every night for a week on this project, here are the assumptions I will use:

First, we’re gonna use NVIDIA’s leading B200 GPU. As of this writing, the B200 is the most advanced GPU on the market designed for frontier AI and multi-trillion parameter models. If you’re building an AI datacenter, this is what you’re gonna use. Also, for the purposes of our calculations, the energy needed to run the B200 is surprisingly reasonable given its processing power. This helps Musk’s case by decreasing how much heat we need to dissipate (it won’t matter in the end).

Second, I assume that all GPU power becomes waste heat. This is silly. But not that silly. In reality, a small fraction does useful work, but for thermal sizing this is appropriate. GPUs are incredibly good at processing bits. But there’s one thing they’re even better at: making stuff hot.

Third, I assume the GPUs run at 100% continuously. Real workloads vary. Training runs hot. Inference can be lower. This is worst-case for thermal but optimistic for utilization economics. Why? Because when you’re engineering a system, this is what you do. You prepare for 100% load and then make risk decisions from that point. You don’t build a bridge assuming it’ll never see a windy day. Well, you do if you’re the Tacoma Narrows Bridge engineers. But that’s not me.

Fourth, we’re gonna start with only one GPU per satellite. This is a ridiculous assumption. But again, to make this more approachable, it’s necessary. Don’t fret! Once I build the model for a single GPU, I’ll make things more complicated and build a model for multi-GPU satellites. Things get messy and nonlinear at that point so I just barely scratch the surface of a multi-GPU satellite. Again, it doesn’t matter in the end.

Fifth, I assume terrestrial GPU hardware works in space (it doesn’t). I don’t add mass for radiation hardening, which could be substantial (2-10× for critical components) or require design changes. This would all increase thermal density and other subsystem power requirements. So this is another conservative assumption in Musk’s favor. You’ll notice throughout that I give a lot of participation trophies to Mr. Musky. What can I say, I’m a generous guy when pulling down your pants to show your ass to the class.

Sixth, I’ll do my best to cite sources for hard numbers. Where I’ve estimated, I make the most conservative estimate that is reasonable. See, though I’m making a satire out of Musk, I’m really handicapping this in his favor. I think that’s pretty generous. Please don’t hurt me.

There will be more assumptions listed in line with my analysis. For transparency, I try to explain them and why I made the choice I did. They distract a bit from the analysis, but it’s also an opportunity for me to be snarky.

Setup complete. Let’s get to part one, building a reference architecture for our Spaceballs Datacenter satellite (“BallSat” for short).

Part 2. Comb the Desert!

The constraining factors with satellites have a nice little acronym, SWaP (Size, Weight, and Power). All of those factors affect a fourth constraint, Heat. We will calculate all four to figure out what to expect with our BallSat. We’re gonna build a table that looks like this:

| BallSat Subsystem 1 | BallSat Subsystem 2 | BallSat Subsystem N | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Size | |||

| Weight | |||

| Power | |||

| Heat |

Each BallSat consists of six subsystems: the GPU computing subsystem (Mr. Computer), thermal control subsystem (Mr. Radiator), electrical power subsystem (Mr. Solar), attitude determination and control subsystem (Mr. Engine), communication subsystem (Mr. Talkie), and the caffeine transport subsystem (Mr. Coffee). This is an oversimplified model of a spacecraft. Here’s NASA’s description of all spacecraft subsystems. But we have the big stuff, which is sufficient for an estimation. We will calculate SWaP and Heat for each subsystem.

We’re launching all this up there, aren’t we? That costs money and is directly related to weight. Unfortunately, Daddy didn’t buy us a brand new, white Mercedes, 2001 SEL Limited Edition. Moon roof, all leather interior. At a very good price.

No, but we do have the Falcon Heavy and, someday, the Starship. According to CSIS, it costs $1,500 per kilogram to launch on the Falcon Heavy. That’s a very good price. With Starship, that could get down to $500. But let’s stick with the verified number and bump it down to $1,000/kg to be nice to Mr. Musky. We’ll invoice his Nazi Pedo Porn Bar called X to cover the difference.

Part 3. I’m Having Trouble with the Radar, Sir.

Now we’re gonna figure out the thermal output of an NVIDIA B200 GPU. This is the easy part. Remember assumption two?

According to the B200 spec sheet, it draws 1,000 watts. Hell yes. I love round numbers.

Okay, okay, fine. That’s not totally right. There’s actually a more advanced fullspec B200 that draws 1,200 watts. But layoff, alright? I like 1,000. We’re sticking with 1,000. Mr. Musky needs all the help he can get.

Ooo this is a fun aside. What character from Spaceballs would Musk be? Definitely not Dark Helmet. He doesn’t have the charisma (or the stature). Write-in your thoughts.

1,000 watts of power equals 1,000 watts of heat. We need a thermal system that can handle 1kW.

CHECKPOINT autosaved. Would you perhaps like to collect this healthpack and extra ammo before proceeding? Yeaaaa, you should probably grab those grenades too…

Part 4. Who Made this Man a Gunner?

Allow me to introduce you to my good friends, Messrs. Stefan and Boltzmann. They came up with this:

q = ε × σ × A × (T_hot⁴ – T_sink⁴)

Where:

q = heat rejected (W)

ε = emissivity (dimensionless, 0-1)

σ = Stefan-Boltzmann constant

A = radiator area (m²)

T_hot = radiator surface temperature (K)

T_sink = effective sink temperature (K)

What does it do? I don’t know. Poke it with a stick or something.

Plug and Chug

This is where most people’s brains start melting. Unlike the GPU. The GPU’s fine. The GPU doesn’t care about your feelings.

We know q (that’s 1kW). The constant σ is 5.67E-08 W/(m²·K⁴). For radiator emissivity (ε) we’ll use a generous midpoint of NASA’s values from their thermal control manual, which is 0.75. Target radiator surface temperature (T_hot) is 323 K. Why? Because 50°C AKA 323 K AKA 122°F is a realistic radiator temperature for liquid-cooled datacenter GPUs. Real systems run coolant at 40-50°C inlet and 50-60°C outlet. The GPU junction can hit 87°C before throttling, so there’s plenty of thermal headroom. This is generous to Musky (lower temps = safer for the GPU = bigger radiators). We’re gonna be verrrrry generous to Musky during this exercise.

Effective sink temperature (T_sink) requires some explanation. I’m going to use 230 K, which is generous for LEO and makes some sense because it accounts for realistic operational constraints like non-ideal pointing, earth view factor during orbit, etc. Here are a bunch of reference numbers I found in my research:

| Radiator Orientation | Effective T_sink | Rationale | Confidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Space-facing (zenith) | ~3-4 K (deep space) | No Earth view, minimal solar | High |

| Earth-facing (nadir) | ~150-250 K | Earth IR dominates | Medium |

| Average/tumbling | ~200-230 K | Mixed view factors | Medium |

Solve for Area.

1000 W = 0.75 × 5.67×10-8 × A × (323⁴ – 230⁴)

A = 2.91 m²

So every GPU requires 2.91 square meters of radiator just for the GPU itself. For those of you who think in freedom units, that’s a square about 5.6 feet per side, roughly the size of a beer pong table. Your GPU needs a regulation beer pong table’s worth of radiator. In space. Just to not explode and melt your face. Red solo cups not included.

More importantly, that’s PRECISELY 1 square smoot. Did not plan this. Math truly IS the language of God.

What about weight?

I estimate a B200 GPU module to weigh 3.2 kg. It doesn’t really matter that much, so I’m not gonna show the work. It’s not published anywhere that I could find, but I did look at comps.

What about the radiator? NASA’s thermal control panels for a lunar habitat weigh 14 kg/m2 and the deployable version for satellites weighs 12 kg/m2. But this is Elon we’re talking about. Surely SpaceXai can do better. How about 10 kg/m2? Bet.

But that’s not the entire Mr. Radiator, now is it? We need pipes, heat transfer materials, cold plates and interfaces. We’re gonna use a pumped loop system because apparently heat pipes don’t scale past a few kilowatts per unit, and someday BallSat is gonna grow up to dozens of kilowatts per unit (just you wait). So I’ll use numbers from this Space Radiator for Single-Phase Mechanically Pumped Fluid Loop. Lot of big fancy words in that. Seems legit.

The thermal transport system runs about 30 kg/kW. We also need the coldplates and interfaces, which are about 1.5 kg per GPU. Total weight of TCS is 30 kg/kW + 10 kg/m² × A + 1.5 kg × number_GPUs

For a single 1 kW GPU with 2.91 m² radiator: 30 + 29.1 + 1.5 = 60.6 kg.

| Mr. Computer | Mr. Radiator | |

|---|---|---|

| Size | Assume 0 | 2.91 m²/kW (GPU heat only) |

| Weight | 3 kg/GPU | ~60 kg/kW (GPU heat only) |

| Power | 1 kW | Assume 0 |

| Heat | 1 kW | Assume 0 |

Now we’re getting somewhere.

Hmmm… to produce 1,000 watts of heat, we need to use 1,000 watts of power, which means we need to produce 1,000 watts of electricity. This is starting to feel circular…

We can’t create electricity from nothing (pesky thermodynamics). That means solar power. So let’s look at Mr. Solar next.

Part 5. Yogurt? I Hate Yogurt! Even with Strawberries.

Mr. Solar consists of solar panels, inverters, batteries, and wiring. That’s a lotta hooch.

But before we dive in, we need to talk about something I glossed over in the last section. Remember how I said Mr. Radiator needs to dissipate 1 kW of heat? Yeah, I lied. Well, not lied exactly. More like… I was being too nice to Musky.

See, Mr. Radiator doesn’t just magically move heat around. He needs pumps. Those pumps need electricity. That electricity becomes heat. And Mr. Solar? He’s got power conditioning equipment, DC-DC converters, regulators, all that jazz. They’re about 95% efficient. Where does that other 5% go? Heat. The batteries charging and discharging during eclipse? About 5% round-trip losses. Heat. ADCS (that’s Mr. Engine, we’ll meet him later)? He needs power to spin his little gyroscopes. Heat.

Forget turtles. It’s heat all the way down.

For every 1 kW of GPU heat, you’re actually generating about 1.26 kW of total heat when you account for all the subsystems. That’s a 26% overhead. Which means our radiator calculation from Part 4? Too small. By 26%.

But you know what? I’m gonna ignore this for now. Why? Because I already gave Musky the benefit of the doubt on like twelve other things, and frankly, 26% isn’t going to save him. The math is about to get ugly. Like Princess Vespa’s old nose ugly.

The Sun: Nature’s Space Heater

Fun fact: the Sun blasts Earth with about 1,361 watts per square meter. This is called the solar constant, and unlike Musk’s promises, it actually is constant. Well, technically it varies between 1,317-1,414 W/m² depending on where Earth is in its orbit, but NASA says 1,361 W/m², so that’s what we’re using.

“Great!” you might think. “I need 1 kW, the Sun provides 1,361 W/m², so I need less than a square meter of solar panel!”

Oh, sweet summer child. Buckle up.

Efficiency: The Universe’s Way of Saying “LOL No”

Solar panels don’t capture all that sunlight. Not even close. Here’s what happens to those beautiful photons. Solar cells can get about 30%. Packing limitations capture 87% of that. Pointing problems (hey, no judgment here) gives you 90% of that. Wiring, which adds resistance, means you see about 95% of that.

Multiply it together and weep: 22%. The Sun gives us 1,361 W/m². We get 303. The universe hates efficiency almost as much as Musk hates unions.

To generate 1 kW, we need: 1,000 W ÷ 303 W/m² = 3.3 m² of solar array.

“That’s not so bad!” you say. “About the same as the radiator!” Oh, we’re not done.

Total Eclipse of Your Heart (not Elon’s, don’t think he has one of those)

Here’s the thing about Low Earth Orbit: you’re going around the Earth every 90-ish minutes. And about 35 of those minutes? You’re in Earth’s shadow. No Sun. No power. Just you, your GPUs, your VHS of Spaceballs from 1992, and the cold void of space where no one can hear you scream about how Spaceballs is the perfect movie.

Well, not cold exactly. Your GPUs are still pumping out heat. They don’t care about your eclipse. They’re needy like that. Mr. Solar would like to file a complaint with HR about the eclipse situation.

So you need batteries. And batteries are heavy. Let’s do the math:

Orbital period: ~92 minutes (at 400km altitude, ISS territory)

Eclipse duration: ~35 minutes

Sunlight: ~57 minutes (62% of orbit)

During those 57 minutes of sunlight, you need to:

- Power your GPU (1 kW)

- Charge batteries for the 35-minute eclipse

That means your solar arrays need to produce: 1 kW × (92 min ÷ 57 min) = 1.61 kW

New solar array area: 1,610 W ÷ 303 W/m² = 5.3 m²

We went from 3.3 m² to 5.3 m² just because the Earth occasionally gets in the way. Thanks, Earth. What have you done for me lately?

Batteries: The Heavy Part

How much battery do we need for 35 minutes of 1 kW operation? Energy required: 1 kW × (35/60) hr = 0.583 kWh

But wait. You can’t drain a battery to zero. Well, you can, but then it dies. According to NASA’s Power Systems State of the Art, if you want them to last more than a few thousand cycles, space-qualified batteries should only be discharged to about 70% depth-of-discharge, or DoD. But let’s rename it to depth-of-wischarge and call it DoW. Nah, nevermind. That looks DUMB, Pete.

In LEO, you’re doing ~5,500 eclipse cycles per year. Batteries are not cheap to replace when you’re 400 km up. Battery capacity needed: 0.583 kWh ÷ 0.70 = 0.83 kWh

What about weight? Space-qualified Li-ion batteries run about 150-200 Wh/kg at the system level (less than your Tesla because they’re actually rated for thermal cycling). Let’s say 175 Wh/kg.

Battery mass: 833 Wh ÷ 175 Wh/kg = 4.8 kg

Solar Array Mass: Also The Heavy Part

According to NASA, modern deployable solar arrays like the ISS iROSA run about 3 kg/m² including deployment mechanisms. Solar array mass: 5.3 m² × 3 kg/m² = 15.9 kg

Adding it up:

- Solar array mass: 15.9 kg

- Battery mass: 4.8 kg

- Total Mr. Solar: 20.7 kg

Let’s call it 21 kg.

| Mr. Computer | Mr. Radiator | Mr. Solar | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Size | Assume 0 | 2.91 m² | 5.3 m² |

| Weight | 3 kg | 60 kg | 21 kg |

| Power | 1 kW | Assume 0 | 1.6 kW peak |

| Heat | 1 kW | Assume 0 | Assume 0 |

So far, one GPU requires: 3 + 60 + 21 = 84 kg of satellite mass and 8.2 m² of deployed area (radiator + solar). We still have ADCS and structure to go.

At $1,000/kg to launch, that’s already $84,000 just for thermal and power, before we add ADCS, structure, and the GPU itself! The B200 costs about $30,000-40,000. The supporting infrastructure costs more than three times the hardware.

We still have Mr. Engine and Mr. Talkie to go. And Mr. Coffee, of course! I always have coffee when I do math, YOU KNOW THAT! EVERYBODY KNOW’S THAT!

Now that I have my coffee, I’m ready to do Mr. Engine. This is going great.

Part 6. They’ve Gone to Plaid!

Mr. Engine is the attitude determination and control subsystem, or ADCS. His job is to point things where they need to be pointed. In the biz, we refer to the ADCS as the cialis of the BallSat.

Nah I just made that up. I have no idea how they refer to the ADCS. I’m a cyber nerd who just happens to like space stuff. Space stuff 2015, amiright?

“Wait,” you say. “It’s space. There’s no friction. Once you point something, it stays pointed. Why do I need a whole subsystem for this?” Oh, you sweet, naive, ground-dwelling creature. Oh you inconsequential mud waddling worm. You absolute dunce. You orangutan. Allow me to introduce you to the concept of disturbance torques.

Why Space Hates You

Your satellite so far has ~8 m² of deployed area (radiators + solar panels). That’s a lot of surface area for the universe to mess with. Here’s what’s constantly trying to spin your satellite like a rotisserie chicken:

Solar radiation pressure: Photons have momentum. When they hit your solar panels, they push. Unevenly. Because nothing in space is ever symmetric.

Gravity gradient: Earth’s gravity is slightly stronger on the side of your satellite closer to Earth. This creates a torque trying to point your longest axis toward the ground. Helpful if that’s what you want. Annoying if it isn’t.

Atmospheric drag: “But there’s no atmosphere in space!” There’s almost no atmosphere. At 400 km, there’s still enough wispy gas to create drag. And if your center of pressure isn’t perfectly aligned with your center of mass (it isn’t), you get torque.

Magnetic field interaction: Any residual magnetism in your satellite interacts with Earth’s magnetic field. More torque.

All of these are small. But small torques integrated over time become big angular velocities. And then your solar panels are pointing at the Moon, your radiators are face-first into the Sun, and your GPU is having a very bad, very hot, melty sorta day.

Reaction Wheels: Spinning to Stay Still

The most common solution is reaction wheels. These are flywheels that spin inside your satellite. Speed one up, and conservation of angular momentum makes your satellite rotate the opposite way. It’s like spinning on an office chair while holding a bicycle wheel. Where’d you get the bicycle wheel? And more importantly, where the hell is the shrimp alfredo that I left in the breakroom, JANET?!

For a small satellite with ~8 m² of deployed area, you need a modest reaction wheel system. Looking at Blue Canyon Technologies and similar vendors, a basic 3-axis reaction wheel assembly runs about:

- Mass: 5-10 kg

- Power: 10-30 W (continuous, more during maneuvers)

But here’s the problem: reaction wheels can only store so much angular momentum before they saturate. ‘Saturate’ is engineer-speak for ‘I’ve given her all she’s got, Captain!’ except nobody’s coming to rescue you.

Momentum Dumping: The Space Toilet

You’ve got two options:

Magnetic torquers – the fiber of the spaceflight diet: Electromagnets that push against Earth’s magnetic field. Cheap, lightweight (1-2 kg), no consumables. But they’re weak and only work well in LEO. Let’s be generous and say this works for our little satellite.

Thrusters – space-MiraLAX: Squirt some propellant, create torque. Works great, but now you need propellant tanks, plumbing, and you eventually run out. We’ll ignore this for now because I’m still being nice to Musky.

Mr. Engine Summary

For our single-GPU BallSat:

| Component | Mass | Power |

|---|---|---|

| Reaction wheels (3-axis) | 8 kg | 20 W |

| Magnetic torquers | 2 kg | 5 W |

| Sensors (star tracker, IMU) | 3 kg | 10 W |

| Processing electronics | 2 kg | 5 W |

| Total Mr. Engine | 15 kg | 40 W |

Now, 40 watts might not sound like much, but remember, that’s 40 watts that also becomes heat, needs to come from Mr. Solar, and creates another little bit of mass we need to launch. I’m going to ignore that for now and be generous to Musky. It’s like the government handing him a tax write-off. Standard procedure.

| Mr. Computer | Mr. Radiator | Mr. Solar | Mr. Engine | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size | Assume 0 | 2.91 m² | 5.3 m² | Assume 0 |

| Weight | 3 kg | 60 kg | 21 kg | 15 kg |

| Power | 1 kW | Assume 0 | 1.61 kW | 40 W |

| Heat | 1 kW | Assume 0 | Assume 0 | Assume 0 |

Running total: 3 + 60 + 21 + 15 = 99 kg per GPU with a surface area of 8.1 m2

We’re closing in on the $100,000 launch cost threshold per GPU. And we haven’t even added communications or structure yet.

The Scaling Problem AKA CHEKHOV’S GUN OF THIS ENTIRE HOOTENANNY. DO YOU SEE IT? THE GUN? IT’S SITTING RIGHT THERE. ON THE TABLE.

Here’s the thing about Mr. Engine: it scales badly with size.

Double your deployed area, and you roughly double your disturbance torques. But moment of inertia scales with mass times distance squared. So when you go from a cute little ~8 m² satellite to a monstrous multi-GPU beast with hundreds of square meters of deployed panels… Your reaction wheels can’t keep up.

You need control moment gyroscopes, the beefy cousins of reaction wheels. The ISS uses CMGs. They weigh about 128 kg each. And you need at least four of them.

But that’s a problem for future us. Right now, we’ve got one GPU, 99 kg of BallSat, and Mr. Talkie still waiting in the wings.

Part 7. When Will Then Be Now?

Mr. Talkie is the communications subsystem. His job is deceptively simple: get data to the GPU, and get results back down.

“Simple!” you say. “We’ve had radios for over a century! Marconi figured this out in 1901!”

Marconi was not trying to send gradients from a trillion-parameter neural network through 400 kilometers of vacuum while traveling at 7.66 kilometers per second. Marconi had it easy. Marconi didn’t have to deal with link budgets or the FCC.

The Contact Time Problem

Fun fact about LEO satellites: they’re never in one place for long. At 400 km altitude, you’re zipping around Earth every 92 minutes. A ground station can only see you for about 8-12 minutes per pass, and you might only get 4-6 good passes per day over any given station.

That’s maybe 30-50 minutes of contact time per day. Per ground station.

“So build more ground stations!” Sure. You know who has a lot of ground stations? SpaceX, actually. Starlink has a decent ground network. Let’s be generous and say you can achieve 4 hours of ground contact per day through a network of stations. That’s still only 17% of the time you’re actually connected to Earth.

The other 83% of the time? Your GPU is up there. Alone. Doing math. Unable to tell anyone about it. Now that I think about it, sounds like me…

This is suboptimal. This is, in fact, the opposite of optimal.

The Bandwidth Problem

Let’s talk about how much data a GPU actually needs.

For training large models, GPUs don’t work alone. They work in clusters, constantly sharing gradients, activations, and weights with each other. According to NVIDIA’s own documentation, a single B200 can require 400-3,200 Gbps of interconnect bandwidth between GPU clusters when doing serious distributed training.

I could make this worse on Musk because GPU-to-GPU communications inside a cluster actually needs up to 14,400 Gbps, and our BallSat is only one GPU, but let’s stick with the generous numbers. Let me write that again for the people in the back: up to 3,200 gigabits per second.

You know what the most exquisite commercially available communication satellite can do? Well that would be ViaSat-3 and its entire capacity is about 1,000 Gbps. On a good day (it hasn’t had many of those). With terminals that cost as much as a luxury home in Malibu.

The entire satellite cost $700 million. And that’s only enough bandwidth for approximately half of one B200’s communication needs. ViaSat-3 is also 6,400 kg, has a wingspan larger than a 737 jetliner, and is located 22,236 miles away in Geosynchronous orbit. A more reasonable facsimile is a Starlink satellite in LEO, which can do about 25 Gbps.

So we’re only short by a factor of… **checks notes** …128x. Cool cool cool cool cool.

“But wait!” you say. “Maybe each satellite can do inference instead of training! Inference needs less bandwidth!”

Sure. Inference needs less bandwidth. You could probably get away with 1-10 Gbps for inference workloads. That’s actually achievable with modern satellite comms. You know what else inference needs? Customers. Who send you requests. And expect responses. In real-time. While your satellite is on the other side of the planet from them. The bandwidth thing is a giant red herring. The real problem is latency. Latency kills user experience faster than Barf kills a box of Milk Bones.

We’ll come back to the latency problem in a second. First, let’s figure out what Mr. Talkie actually weighs.

Communications Hardware

For our single-GPU satellite, we don’t need 3,200 Gbps. We just need enough bandwidth to:

- Receive commands and software updates (kilobits per second)

- Send telemetry and health data (kilobits per second)

- Maybe, maybe, do some useful data transfer (let’s say 100 Mbps to be nice)

For this, a basic Ka-band or X-band system will do. Looking at commercial small satellite communication systems:

| Component | Mass | Power |

|---|---|---|

| Transceiver (Ka-band) | 3 kg | 30 W |

| Antenna (steerable patch/horn) | 2 kg | 5 W |

| Waveguide, cables, brackets | 1 kg | - |

| Total Mr. Talkie | 6 kg | 35 W |

That’s pretty light, actually! Communications hardware has gotten remarkably compact. Thank you, smartphone industry.

| Mr. Computer | Mr. Radiator | Mr. Solar | Mr. Engine | Mr. Talkie | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size | Assume 0 | 2.91 m² | 5.3 m² | Assume 0 | Assume 0 |

| Weight | 3 kg | 60 kg | 21 kg | 15 kg | 6 kg |

| Power | 1 kW | Assume 0 | 1.61 kW | 40 W | 35 W |

| Heat | 1 kW | Assume 0 | Assume 0 | Assume 0 | Assume 0 |

Running total: 3 + 60 + 21 + 15 + 6 = 105 kg per GPU.

At $1,000/kg, that’s $105,000 to launch a one-GPU BallSat. Plus the GPU itself ($35,000). Plus ground infrastructure. Plus operations. Plus insurance. Plus… you get the idea.

The Latency Problem

I promised we’d come back to this.

Even when your satellite is in contact with a ground station, there’s latency. At 400 km altitude, the round-trip time for a signal is about 2.7 milliseconds just from the speed of light. Add in processing delays, routing through ground networks, and suddenly you’re looking at 20-50 milliseconds of latency.

“No problem!” you say. “We’ve got that latency at home!” you claim. And you’d be right, that doesn’t sound like much. It’s about the same latency as an internet packet traveling from a home outside Annapolis, MD to a datacenter in New York on a cold winter day. Yes I just checked this. Yes, I know how to check this without asking AI. As I said earlier, I’m a cyber nerd, not a space dweeb.

But for distributed GPU training, where thousands of GPUs need to synchronize gradients many times per second? It’s an eternity. Terrestrial data centers connect their GPUs with sub-microsecond latency. We’re talking a difference of 10,000x or more.

Light speed is too slow! We’re gonna have to go right to… still too slow. Until Musky figures out how to break the speed of light (he can’t, Einstein), this is INESCAPABLE.

Real story: I once did a project with a research lab in the New Mexico desert. They wanted to use a datacenter in California for production systems. They kept having latency issues that rate-limited production. They asked us to look at the problem again and again and again. Eventually, we pulled out a map and a ruler. Turns out, the latency was literally caused by the speed of light. Sorry, bub. Can’t fix that.

This is why you can’t just strap GPUs to satellites and call it a distributed training cluster. The physics of latency and bandwidth make it fundamentally incompatible with how modern AI training actually works.

But hey, maybe Musk has a plan. Maybe each satellite does its own thing independently. Maybe it’s for inference only. Maybe it’s for some application that doesn’t exist yet.

Or maybe he’s just saying random inane things to juice his stock price and generate headlines.

¯\_(ツ)_/¯

Inter-Satellite Links: The Even Harder Problem

“What if the satellites talk to each other?” you ask. “Then they don’t need ground stations!”

Congratulations, you’ve invented the mesh network. Starlink uses these. They’re called inter-satellite links, and they’re actually really cool technology that solves absolutely none of our problems.

Here’s how it works: laser-based optical terminals that can achieve 10+ Gbps between satellites. Sounds great! Let’s add them!

To participate in a mesh network, each satellite needs 4+ optical terminals for decent connectivity. Per terminal: 2-5 kg, 20-50 W. For our single-GPU satellite, that’s:

| Addition | Mass | Power |

|---|---|---|

| 4 optical terminals | +12 kg | +100 W |

| More solar panels | +5 kg | — |

| More batteries | +2 kg | — |

| More radiator | +3 kg | — |

| Total mesh tax | +22 kg | +100 W |

Our ~105 kg satellite just became ~127 kg. That’s a 21% mass increase to gain the ability to… **checks notes** …still have latency problems.

In fact, your latency problem is now worse. Congrats, you have died of latency…

See, here’s the thing. You’re not eliminating the speed-of-light problem. You’re adding hops. Each satellite-to-satellite link adds processing delay. Route through five satellites to reach your destination? That’s five times the fun! Your 20 ms latency just became 50 ms. Your distributed training cluster just became a distributed waiting cluster.

But wait (just like your satellites), it gets better! To make a mesh network that can actually route traffic, you need hundreds of satellites. Thousands, ideally. Each one is now 21% heavier. Your constellation mass budget just exploded.

And you STILL can’t do distributed training because you STILL don’t have 3,200 Gbps of bandwidth. You have 10 Gbps. Per link. Shared across the mesh. You’ve now built a very expensive, very laggy, very heavy network that can maybe, maybe, do inference for customers who don’t mind waiting.

This is like solving a house fire by adding more houses. On fire.

We’re not adding mesh networking to our model. Not because it doesn’t work. It does work, beautifully, for Starlink’s actual use case of internet connectivity. But for GPU training? It’s like putting racing stripes on a refrigerator. Looks cool. Doesn’t help. Although, honey, if you’ve actually made it this far, I swear it will look cool. Please let me put racing stripes on our refrigerator…

Mr. Talkie Summary

For basic Earth communication: 6 kg, 35 W

The mass isn’t the problem. The problem is the theory of special relativity. The speed of light isn’t fast enough. The available bandwidth isn’t wide enough. And the contact time isn’t long enough.

Mr. Talkie isn’t heavy. He’s just… not very useful for what Musk wants to do. Oh well.

Let’s move on to structure. Mr. Frame has been waiting patiently, and he’s the only one in this satellite who isn’t actively making things worse.

Part 8. Funny, She Doesn’t Look Druish.

We’ve been ignoring something important. All these subsystems (Mr. Computer, Mr. Radiator, Mr. Solar, Mr. Engine, Mr. Talkie) need something to hold them together. They can’t just float in space in a loose confederation of components, hoping for the best. That’s not a satellite. That’s a debris field with dreams.

Enter Mr. Frame, the yet-unnamed structural subsystem.

Mr. Frame keeps everything from becoming a very expensive game of 52-microchip pickup. In space. Where you can’t pick anything up.

Structural Mass Fraction

Here’s a handy rule of thumb from spacecraft engineering: structure is typically 15-25% of your satellite’s dry mass.

Why such a range? It depends on how elegant your design is. A beautifully optimized satellite with heritage components and an experienced team might hit 15%. A first-of-its-kind design with lots of deployables and thermal complexity? Closer to 25%.

What do we have? A first-of-its-kind design with lots of deployables (~8 m² of panels!) and thermal complexity (pumped fluid loops! cold plates!).

Let’s use 20%. That’s being nice to Musky. Generous, even. At this point I’m basically handing him the keys to the datacenter and a participation trophy. Just like the US Government handed him tax write-offs for all his companies. But let’s keep using the generous numbers for a bit longer. Because it doesn’t matter. Even with all my handouts to Musky, the math still doesn’t work.

The Math Doesn’t Math

Our component masses so far:

| Subsystem | Mass |

|---|---|

| Mr. Computer | 3 kg |

| Mr. Radiator | 60 kg |

| Mr. Solar + Batteries | 21 kg |

| Mr. Engine | 15 kg |

| Mr. Talkie | 6 kg |

| Component Total | 105 kg |

Structural mass at 20%: 105 kg × 0.20 = 20 kg

Final Tally: One GPU, One BallSat, A Whole Lot of Ass’ing

| Mr. Computer | Mr. Radiator | Mr. Solar | Mr. Engine | Mr. Talkie | Mr. Frame | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size | Assume 0 | 2.91 m² | 5.3 m² | Assume 0 | Assume 0 | Assume 0 |

| Weight | 3 kg | 60 kg | 21 kg | 15 kg | 6 kg | 20 kg |

| Power | 1 kW | Assume 0 | 1.61 kW | 40 W | 35 W | Assume 0 |

| Heat | 1 kW | Assume 0 | Assume 0 | Assume 0 | Assume 0 | Assume 0 |

Total BallSat mass is 125 kg and total deployed area is 8.1 m². This is a big satellite for a single GPU. About the size of a minivan and the weight of 125,000 jelly beans.

The Cost of One BallSat

| Item | Cost |

|---|---|

| Launch (125 kg × $1,000/kg) | $125,000 |

| GPU (B200) | $35,000 |

| Satellite components (bargain bin) | $75,000 |

| Total per BallSat | $235,000 |

And that’s being extremely generous on the hardware costs. Real satellite costs are often 10x higher. But sure, let’s pretend SpaceX has magical cost reduction fairies. It’s fine. I’m fine.

$235,000 per GPU.

For comparison, you can rent a B200 in a terrestrial datacenter for about $5 per hour. At $235,000, you could rent that GPU for 47,000 hours. That’s 5.4 years of continuous operation.

And your terrestrial GPU has:

- Sub-microsecond latency to other GPUs

- 3,200 Gbps cluster-to-cluster bandwidth

- 14,400 Gbps GPU-to-GPU bandwidth

- 100% uptime (no eclipses)

- Easy maintenance and upgrades

- Air conditioning that actually works

Your space GPU has:

- None of that

- A nice view

But Wait, There’s More!

We haven’t even talked about:

Propulsion for orbit maintenance (LEO satellites need periodic boosts to avoid reentry). Redundancy (satellites fail; do you have backups?). Ground operations (someone needs to monitor and command these things 24/7). Insurance (space is risky; insurers know this and charge you for it). Regulatory costs (spectrum licenses, orbital debris mitigation plans, etc.). End-of-life disposal (you can’t just leave dead satellites up there forever… well, you can, but people get mad).

Each adds cost. Some add mass. All add sadness.

What I Swept Under the Rug

Confession time.

Remember all those “Assume 0” entries in my tables? All those times I said “we’re ignoring this” or “Musky gets another freebie”? Yeah, those add up. I’ve been running a simpler model to keep things readable, but I also built a more complex model that accounts for all the thermodynamic sins I’ve been committing.

The results are… not great for Musky.

See, every subsystem needs power. Power becomes heat. Heat needs radiators. Radiators need structure. Structure adds mass. Mass adds engine needs. Engines need power. Power needs more solar panels. Solar panels need batteries for eclipse. Batteries add mass. Mass needs more structure. Structure needs more—

You get the idea. It really IS turtles all the way down, except the turtles are on fire and each turtle makes the next turtle heavier.

Here’s what I glossed over:

Sin #1: I ignored the subsystem power draw. Mr. Engine doesn’t run on hopes and dreams. Those reaction wheels need 40W continuously. Comms needs 35W. The thermal pumps that move heat to the radiators? 3% of whatever heat you’re moving. Power conditioning losses? 5% of everything. Battery round-trip efficiency during eclipse? Another 5% loss. All that power has to come from somewhere. Suddenly your “1 kW GPU” satellite actually needs 1.6 kW continuous. And it all becomes heat.

Sin #2: I ignored the cascade effect. For every 1 kW of GPU heat, you’re actually generating about 1.26 kW of total heat. That’s a 26% overhead. Which means my radiator calculation? Too small. My solar panels? Too small. My batteries? Too small. Bigger batteries mean more solar to charge them. More solar means more area. More area means bigger Mr. Engine. Bigger Mr. Engine means—screaming internally.

Sin #3: I ignored avionics. Flight computers, data handling, housekeeping. Real satellites need bus systems that weigh 50-100 kg. I pretended they don’t exist.

Sin #4: I assumed ADCS doesn’t scale with area. For our tiny 8 m² satellite, 15 kg of reaction wheels is fine. But what happens when we add more GPUs and the deployed area grows to hundreds of square meters? Spoiler: bad things happen.

Sin #5: I neglected that designing, building, testing, integrating, launching, and operating this thing costs real money, and that SpaceXai doesn’t have a magic money wand. In reality, building satellites is expensive. BallSat is no exception. I’ve built a more accurate cost model that I will use from here on out. It’s going to make this whole exercise look like Spaceballs 2: A Search for More Money.

If I account for all this properly, our 125 kg satellite becomes 287 kg. Our 8 m² becomes 13 m². Our $235,000 cost becomes $4,700,000!

230% more massive, 162% more surface area, 2000% more expensive. This is a big satellite. 13 m² is about the size of a studio apartment in Tribeca. 287 kg? That’s 290,000 jelly beans. And remember, still only one GPU.

So why did I use the simple model for the walkthrough?

Three reasons:

- Pedagogy. The simple model is easier to follow. You can actually trace the logic without your eyes glazing over. The complex model has formulas referencing other formulas referencing other formulas. It’s accurate, but it reads like a tax return.

- Conservative bias. The simple model is generous to Musk. Everything I ignored made the numbers worse. If the simple model shows the concept is bonkers, the complex model shows it’s even more bonkers.

- It doesn’t change the conclusion. Whether a single-GPU satellite costs $235K or $10M, it’s still absurd compared to $2/hour for terrestrial GPUs. Whether it masses 100 kg or 500 kg, it’s still launching kilograms of space junk for a single GPU. The story is the same. The vibes are the same. The math is just angrier.

But here’s what the complex model does reveal that matters for Part 9:

The fixed overhead.

Think about Mr. Engine and Mr. Talkie. They’re fixed costs. You need them whether you have 1 GPU or 100 GPUs. For a single-GPU satellite, those 21 kg of fixed subsystems represent 21% of your component mass. That’s overhead that gets amortized if you add more GPUs.

“Aha!” you say. “So adding more GPUs makes things more efficient! This is where Musk wins! Synergy! Vertical integration! Friendshoring! Y Combinator!”

Oh no. Oh no no no.

Adding more GPUs does amortize the fixed costs. But it also does something else. Something worse. Something I’ve been foreshadowing since Part 6.

Remember Chekhov’s Gun? The one sitting on the table? Yes that one, right there in front of you. Or that other one, right behind you on the floor. This is America. This room is lousy with guns. Please pick up the gun labeled “Mr. Engine scales badly with deployed area.”

It’s time to pull the trigger.

Part 9. Even in the Future Nothing Works

Who the hell makes a datacenter with a single GPU? I do, that’s who. But let’s also fix that real quick.

Alrighty. One GPU, one BallSat. With my generous assumptions: 125 kg. $235,000. 8 m² of deployed area. Marginal utility at best.

“But surely,” you say, channeling your inner MBA, “economies of scale will save us! What if we put MORE GPUs on each satellite? Amortize those fixed costs! Core competency! Invest in the intangibles. McKinsey has been recommending this for decades!”

You’ve been waiting for this. I’ve been foreshadowing it. The gun is loaded and cocked. Let’s see what happens when we add more GPUs.

The Promise of Scale

Here’s the theory: Mr. Engine (ADCS) and Mr. Talkie (comms) have fixed components. You need sensors, processors, and basic comms whether you have 1 GPU or 100 GPUs. So if you add more GPUs, some of that mass gets spread across more compute. Efficiency!

But here’s the thing, to do this properly, I can’t keep sweeping things under the rug. When you scale up, those subsystem power draws and heat loads become impossible to ignore. So from here on out, I’m using the full model. I built it in Excel. HMU if you want to see it. It gives great helmet.

In the full model, one GPU actually requires 287 kg and 13 m² when you account for everything. Let’s see how that scales to 16 GPUs:

| Subsystem | 1 GPU | 16 GPUs | Scaling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mr. Computer | 3.2 kg | 51 kg | Linear (16×) |

| Mr. Radiator | 140 kg | 1,145 kg | ~8× (heat overhead drops) |

| Mr. Solar | 23 kg | 364 kg | ~16× |

| Mr. Engine | 17 kg | 114 kg | 6.7×! |

| Mr. Talkie + Avionics | 56 kg | 56 kg | Fixed |

| Mr. Frame | 48 kg | 346 kg | 20% of above |

| TOTAL | 287 kg | 2,077 kg | 7.2× (not 16×!) |

Wait, that’s not linear scaling! Total mass went up only 7.2× while GPUs went up 16×! That’s 130 kg per GPU instead of 287 kg. We’re saving 157 kg per GPU! Economies of scale!

Cost per GPU dropped from $4.7M/GPU (full model) to $1M/GPU. That’s a 79% reduction! MBA vindicated! Synergy achieved! Let’s keep going!

Today’s high end datacenter racks hold 64–72 GPUs. So instead of a single GPU BallSat, let’s build something with real capacity. Elon Musk level capacity! The sort of BallSat that could be CEO of eighteen different companies and still find time to scam its way into the White House. Like a 100-GPU BallSat.

| Subsystem | 1 GPU | 100 GPUs | Scaling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mr. Computer | 3.2 kg | 320 kg | Linear (100×) |

| Mr. Radiator | 140 kg | 6,774 kg | ~48× (huh… losing efficiency) |

| Mr. Solar | 23 kg | 2,278 kg | ~99× (wait… what’s going on?) |

| Mr. Engine | 17 kg | 1,411 kg | ~83× (another one?!) |

| Mr. Talkie + Avionics | 56 kg | 56 kg | Fixed |

| Mr. Frame | 48 kg | 2,168 kg | 20% of above |

| TOTAL | 287 kg | 13,006 kg | 45×! |

Wait a minute. Those numbers looked weird! Something happened with our business school case study on economies of scale. But before we investigate further, let’s put that into perspective, shall we?

| Spacecraft | Mass | Area | What It Does |

|---|---|---|---|

| Starlink satellite | 260 kg | 13 m² | Provides internet to people who complain about internet |

| Hubble Space Telescope | 11,110 kg | 57 m² | Discovered that the universe is terrifying and beautiful. Terrifyingly beautiful |

| ISS (entire station) | 420,000 kg | 2,500 m² | Keeps 6 humans alive while they float, do science, and play David Bowie songs on the guitar |

| 100-GPU BallSat | 13,006 kg | 911 m² | Runs slightly more GPUs than a gaming café |

I see your Schwartz is as big as mine… And what do you get for that? A satellite that weighs more than the Hubble Space Telescope and has 16× its deployed area. For one rack’s worth of GPUs. That’s the sort of combination an idiot would have on his luggage.

The Hubble Space Telescope took 12 years and $16 billion to build in today’s dollars. It revolutionized our understanding of the cosmos. It’s one of humanity’s greatest scientific achievements.

Musk’s BallSat runs 100 GPUs. Poorly. With latency. During 62% of each orbit.

I will remind you again, these are still generous numbers.

Let’s try 64 GPUs. That’s a nice round number. A single rack’s worth of GPUs in a terrestrial datacenter.

| Subsystem | 1 GPU | 64 GPUs | Scaling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mr. Computer | 3.2 kg | 205 kg | Linear (64×) |

| Mr. Radiator | 140 kg | 4,362 kg | 31× |

| Mr. Solar + Batt | 23 kg | 1,458 kg | 63× |

| Mr. Engine | 17 kg | 1,084 kg | 64×! Uh oh |

| Mr. Talkie & Avionics | 56 kg | 56 kg | Fixed |

| Mr. Frame | 48 kg | 1,433 kg | 20% of above |

| TOTAL | 287 kg | 8,597 kg | 30× |

IT KEEPS HAPPENING! What’s going on with Mr. Engine and Mr. Solar?

I’ll tell you what. Their Mom has entered the chat. And Mama Bear is furious.

CHEKHOV’S GUN VAPORIZES YOUR ENTIRE CONSTELLATION BUDGET

Like when Lonestar vaporized all the Spaceballs

Here’s what’s happening. At 64 GPUs, your satellite has:

Radiator area: 64 GPUs × ~3.3 m²/GPU (with overhead) = 210 m²

Solar area: 64 GPUs × ~5.8 m²/GPU = 374 m²

Total deployed area: 584 m²

Five hundred and eighty four square meters. That’s a professional basketball court, plus the first few rows of spectators, floating in space, fans trying not to stroke out, BallSat trying not to spin.

And space really wants to spin it. Space also really wants your spectators to stroke out, but we can’t do anything about that right now. Solar radiation pressure scales linearly with area. More area, more photon push. Atmospheric drag scales linearly with area. More area, more wispy-gas-induced torque. Gravity gradient torque scales with the moment of inertia, which scales with mass times distance squared. When your solar panels extend 10+ meters from your center of mass, that squared term gets nasty.

Your cute little 15 kg reaction wheel assembly? It saturates. It’s like trying to balance a broom on your finger, except the broom is 500 feet long and Mega Maid™ is blowing on it.

You need Control Moment Gyroscopes. The ISS uses these. They’re reaction wheels’ beefy, angry Mama Bear. Each one weighs about 128 kg. And you need at least four for redundancy, plus all their associated subsubsystems.

The fixed cost isn’t fixed anymore.

The Scaling Table of Doom

Let’s see how this plays out across different GPU counts:

| GPUs | Total Mass | Total Area | ADCS Mass | ADCS Type | kg/GPU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 287 kg | 13 m² | 18 kg | Reaction wheel (RWA) | 287 |

| 16 | 2,077 kg | 149 m² | 114 kg | Large RWA | 130 |

| 32 | 4,678 kg | 294 m² | 794 kg | CMG cluster | 146 ← CMG kicks in |

| 64 | 8,597 kg | 585 m² | 1,084 kg | Full CMGs | 134 |

The kg/GPU and cost/GPU actually keeps improving slightly as you add more! But look at those absolute numbers. At 64 GPUs, you’re building a 9-ton satellite with almost 600 m² of deployed area. The technical term here is “stupid big.”

The 100,000 GPU Question

Musk filed for a constellation of up to 1 million satellites. I’m going to ignore that.

Let’s be generous and assume he forgot his factors of ten. He has more money than God. He doesn’t need MATH anymore. He meant 100,000 GPUs, not 1,000,000 satellites. That’s about what you’d find in a large terrestrial AI training cluster.

How do we get there? Based on my model, the CMG threshold is about 30 GPUs, so we want to be slightly below that. Engineers hate odd numbers, unless it’s a prime, so let’s try to optimize at 29 GPUs.

| Config | GPUs/Satellite | BallSats | Total Mass to LEO | Total Surface Area |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spaceballs the Datacenter | 29 | 3,449 | 15 million kg | 922,000 m² |

About fifteen million kilograms and one million square meters. To LEO. Every individual BallSat weighs at least 4,311 kg and has a total deployed area of 267 m².

To put that into terms we can actually fathom, that’s 15 billion jelly beans. Once again proving that math is the language of God because that’s precisely how many jelly beans that Jelly Belly produces every year. What? I like jelly beans…

You don’t like jelly beans? Okay, how about blue whales. It’s a well-established fact that space dweebs love blue whales. So that’s roughly 100 fully grown adult blue whales. But can’t infinite improbability drive your way into getting those things up there. You have to use propellant like the rest of us gassy mortals.

That’s also the surface area of 738 olympic swimming pools. It’s one third the area of Central Park. Each satellite is about 270 m² fully deployed, which doesn’t seem so big by itself. Until you consider the following:

Falcon Heavy payload to LEO: 63,800 kg

Number of Falcon Heavy launches needed: ~247

SpaceX’s total launches in 2025: 165

At their current pace, it would take more than a year and a half just to launch the hardware for a single terrestrial data center. Assuming every single launch is dedicated to GPU satellites. Which means no Starlink. No commercial customers. No NASA missions. Just BallSats. BallSats all day, every day.

And that’s before we talk about manufacturing 3,500 satellites, each more complex than anything SpaceX currently builds.

For what it’s worth, I did check if launch was mass constrained or volume constrained. It’s mass. A reasonable estimation for packing density based on data from NASA is ~360 kg/m³. That means our 29-GPU BallSat at 4,311 kg packs down to 12 m³ for launch. We humans are VERY good at folding things.

Another real life story: when I was a grad student at MIT (name drop) I was drinking at a bar (State Park, iykyk) and struck up a conversation with the dude sitting alone next to me. He was folding origami into some bizarre shapes. Unassuming guy. Turns out he was a post-doc and his ENTIRE LIFE was folding. Creating complex algorithms to prove folding efficiencies and how to make things that look big incredibly small. He got into it because his Dad really liked origami. Fifteen years later and this guy is like the world’s foremost expert on folding stuff with applications from spaceflight to microbiology and robotics. Fascinating conversation. Dude is probably a gazillionaire now. MIT is a really cool place to learn weird things. Anyway, back to your regularly scheduled programming.

Falcon Heavy payload fairing volume is 13.1 m tall with a diameter of 5.2 m. That’s 278 m³. So we could technically fit up to 23 BallSats per Falcon Heavy, but that’s too heavy for the heavy. Maximum is 14 BallSats based on weight. 14 BallSats on a Falcon Heavy, 23 BallSats on a Starship. All of the BallSats in our hearts.

I WILL REMIND YOU, AGAIN, THESE ARE GENEROUS NUMBERS.

The Cost Comparison

What does a 29-GPU BallSat cost to build? At this point, I’m tired, you’re tired, we’re all a bit tired. So let’s skip the math. I added up all the estimated hardware costs. I came up with about $25,000,000. Here, Musky, take another free gimme. I’ll give it to you for $20,000,000.

Let’s add up Spaceballs the Datacenter:

| Item | Cost |

|---|---|

| BallSats (3,449 × $20M each) | $69 billion |

| Launch (15M kg × $1,000/kg) | $15 billion |

| Insurance | $5 billion |

| Mission operations (5 years) | $9 billion |

| TOTAL | ~$98 billion |

Even if you said, “Screw physics! Screw the astronomy community! Screw regulations! I’m building the largest BallSats that my mega Starship rocket can handle and I don’t care what the haters and mathematicians say about it!” You’d still end up an ass. Sorry, keyboard cut out there. You’d still end up hitting an efficiency asymptote and spending about $70 billion on your Spaceballs Datacenter. Each BallSat in this constellation would have a deployed area of about half an acre by the way, so that’s wild to imagine.

Here’s the rub. Is this physically possible? Yes. Do we have the technology to make a BallSat? Yes. Will 3,500 BallSats in LEO at 270 m² each piss everyone off? Also yes. Will they be able to process data? Kind of, as long as you don’t mind everything happening slowly. But does any of this make business sense? Absolutely fucking not.

A terrestrial datacenter with 100,000 GPUs costs about $5 billion.

Including the building. And the equipment. And the power plant. And the cooling towers. And a cafeteria. With a salad bar. Your Spaceballs datacenter doesn’t have a salad bar, does it, Musky? Noooo, that marketing ploy was Tesla’s, and apparently it isn’t going very well.

Musk’s Spaceballs Datacenter costs 20× more than the version on good ole’ reliable terra firma.

And it’s worse at everything except “having a nice view.” Cool cool cool cool cool. This is fine. Everything is fine.

I WILL REMIND YOU, YET AGAIN, THAT THESE NUMBERS ARE GENEROUS NUMBERS.

It Gets Worse

I’ve been assuming these satellites work. That the GPUs function in the radiation environment. That the ADCS keeps pointing everything the right way for years.

I’ve been assuming that your thermal subsystem works just as efficiently at 9 m² as it does at 900 m².

I’ve been assuming you can somehow coordinate 100,000 GPUs with 20-50 ms latency and 10 Gbps bandwidth when terrestrial training clusters need sub-microsecond latency and 3,200 Gbps bandwidth.

I’ve been assuming the regulatory environment lets you fill LEO with 3,500+ GIANT satellites, each the size of a single family home.

Friends, I’ve been assuming a lot.

Part 10. Keep Firing, Asshole.

So there it is.

You can put more GPUs on each BallSat. You do get some economies of scale at first. But then the deployed area grows, and the disturbance torques grow, and Mr. Engine calls his mom, and suddenly you’re building Hubble-sized satellites to run a single rack of GPUs.

You can’t engineer your way out of the laws of physics.

Radiators scale linearly with heat. Solar panels scale linearly with power. But the universe’s attempts to spin your satellite scale superlinearly with area. And your ability to fight back scales sublinearly with mass.

You can’t win. The math won’t let you.

Every economy of scale gets eaten by the ADCS monster. Every efficiency gain gets swallowed by the thermal dragon. Every clever optimization gets buried under the weight of batteries and solar panels and structural mass.

Musk’s space datacenter is fundamentally more expensive at every scale.

And that’s before we talk about the latency. And the bandwidth. And the 38% downtime from eclipses. And the radiation. And the maintenance. And the…

You know what? It’s time for Mr. Coffee.

Epilogue.

After working on this for about eight hours, a friend sent me this awesome web app by a guy who’s a real life space engineer, Andrew McCalip! He works at Varda Space. He seems cool. Can we be friends?

Anyway, Andrew’s app analyzes the same thing from a different, more sober lens. Compared to my version, his is your squared-away uncle with a vacation home in Boca. Mine is more like that second cousin with a nonzero chance of fighting the shopping cart guy in a Piggly Wiggly parking lot.

Our numbers are surprisingly close. About as close as you can get with back-of-the-napkin applied forecasting, which is precisely what this piece is an example of.

If you’d like more, I’m leading a workshop on First Principles Applied Forecasting at the RSAC 2026 conference in San Francisco on March 24th. You can learn about it here.